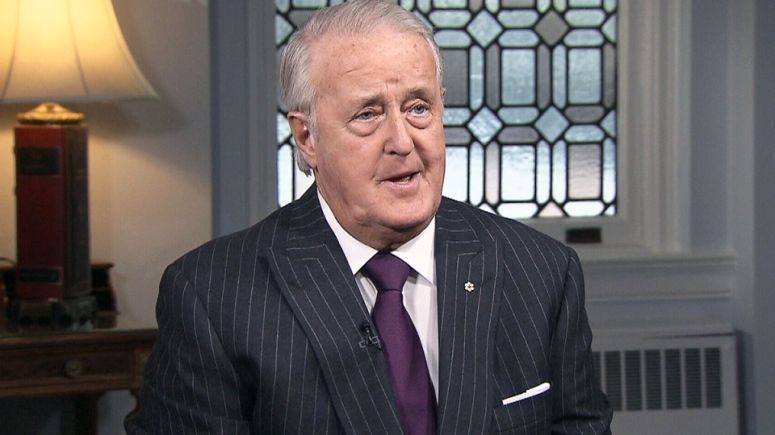

While I’ve written about a few Canadian political leaders on this blog, I have a special relationship with the subject of this post because he happens to represent my first real exposure to a Canadian Prime Minister in real time.

He’s also indirectly responsible for my first newspaper job and my first stint as an editorial cartoonist. And he’s directly responsible for the healthy dose of cynicism that I’ve built up over the past three decades when it comes to electoral politics inside and outside of Canada.

Which is all surprising because, as Brian Mulroney was waging his first campaign as leader of the Progressive Conservative Party, I barely knew he existed in the summer of 1984, even though he had entered Parliament a year earlier by winning a by-election in my home province of Nova Scotia – specifically, in the riding of Central Nova.

I also had no idea that Mulroney was about to preside over one of the single biggest election victories in Canadian history – and then plant the seeds for his party to suffer its worst electoral defeat, the first step in its eventual demise, only nine years later.

Mulroney had already taken a crack at the PC leadership in 1976, coming in third at a convention that saw Joe Clark take the reins. Three years after the end of Clark’s disastrous nine-month PC minority government, Mulroney bested Clark at the 1983 Tory convention, won his Central Nova seat, and spent the next year chipping away at the tired, rotting hulk of the Liberal Party of Canada.

Notwithstanding Clark’s error-prone nine months, the Grits had been in power since 1963 and were showing their age. Even Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, having accomplished pretty much everything he wanted to achieve as Canada’s leader, seemed disinterested in its people and its economy, flying around the world on international peace initiatives instead of dealing with the fallout from a recession that kneecapped Canada in the early ’80s.

Trudeau resigned for the second and final time after his famous “walk in the snow” on February 29, 1984. In choosing his replacement, Liberal delegates passed on one of the Prime Minister’s longtime Quebec lieutenants, Jean Chretien, and chose former cabinet minister John Turner, perhaps hoping Canadian voters would view a non-Quebec anglophone more favourably. Buoyed by a brief bump in the polls for his party after he took the reins, Turner called an election for September 4, 1984, exactly three weeks before my eleventh birthday.

It was Trudeau, however, who unwrapped an ugly present for Turner to kick-start the campaign. In the dying days of his rein on power, he appointed an astounding 225 – yes, two hundred and twenty-five – Liberal loyalists to Senate seats, judiciary positions, international embassies and government commissions. According to Gordon Donaldson, the author of the excellent 1986 book Eighteen Men: The Prime Ministers of Canada, Trudeau went a step further and forced Turner to sign a secret letter appointing another 17 “party hacks” after Trudeau left office. (I remain amazed to this day that this was even legally and constitutionally possible.)

This all set the stage for a pivotal exchange between Turner and Mulroney at the nationally-broadcast English-language federal leaders’ debate. The Liberal leader hoped to capitalize on a supposedly-private joke Mulroney made to reporters on the Tory campaign trail, skewering ex-Liberal MP Bryce Mackasey for accepting the ambassador’s job in Portugal – and, using words I’m not prepared to repeat here, comparing patronage to prostitution – but hinting that he would be just as likely to reward PC party faithful if the Tories won. However, as soon as Turner lobbed his grenade, Mulroney – who had met the teenage version of his wife Mila at the Mount Royal Tennis Courts in Montreal – served up an overhead smash that still ranks as one of the most effective knockout punches in Canadian political history.

“I have apologized to the Canadian people for kidding about it; the least you could do is apologize for making those horrible appointments,” Mulroney thundered at Turner, who stammered back: “I had no option.” Cue Mulroney, smelling blood: “You had an option, sir. You could have said, ‘I am not going to do it. This is wrong for Canada and I am not going to pay the price.'” Turner, knowing full well his goose was cooked: “I had no option.”

If that debate moment (available in this YouTube clip) wasn’t damaging enough, Turner sealed his fate with two Cro-Magnon moves against high-powered women in the Liberal Party establishment – specifically, public pats on the gluteus maximus of national party president Iona Campagnola (who, to her credit, immediately slapped him) and that of Quebec party vice-president Lise Saint-Martin Tremblay. It landed the 1984 Canadian election as a lead story on the CBS Evening News, but combined with his debate blunders and the lingering legacy of the latter Trudeau years, it also got Turner a quick end to his time as Prime Minister.

On Election Day, Mulroney’s Tories took 211 of the 282 seats available in the House of Commons at the time. Turner’s Liberals were reduced to a 40-seat Official Opposition rump; until Michael Ignatieff bumbled his way through the 2011 campaign, this would represent the lowest-ever seat total for the organization self-styled as “Canada’s National Governing Party.”

So young Adam, who was barely aware of the basic existence of either Pierre Trudeau or Joe Clark and hadn’t had nearly enough time to acquaint himself with John Turner, was finally going to get a good look at a Canadian Prime Minister for the foreseeable future. His first taste of The Right Honourable Brian Mulroney came when the new Prime Minister pulled a familiar trick for a newly-elected party replacing a long-running, worn-out government: announcing that his first Finance Minister, Michael Wilson, had taken a look at Canada’s finances and surmising that “the situation is rather worse than we had ever anticipated.”

The pattern frequently repeated itself throughout Mulroney’s two majority-government terms. Whether the national crisis of the day was Canada’s ballooning debt (which Mulroney and Wilson increased by 40 per cent during the Tories’ first four years in office), Western alienation, the troubled Atlantic fishery, the threat of Quebec separatism, or the arrival of a second recession in the early ’90s, the new Prime Minister stuck to a familiar theme: It’s all Trudeau’s fault. Receiving a scathing report from the federal Auditor-General in late 1992, eight years after taking power, Mulroney was still using phrases like “we inherited this mess”; upon his retirement from politics a few months later, a political cartoonist predicted that Mulroney’s official statue would feature a schoolboy-sized version of The Boy From Baie Comeau, aiming a slingshot at an adjacent statue of a majestic-looking Trudeau, because “that’s how he wanted to be remembered.”

I remember Brian Mulroney for several reasons, few of them positive. (I’ll tackle some of them in future blog posts, including the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement, the Meech Lake and Charlottetown constitutional accords, and the gutting of VIA Rail’s Atlantic Canadian service. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.)

To be fair, one reason I remember Brian Mulroney is his passionate defence of his stand against the reinstatement of capital punishment during a free vote on the issue in 1987 in the House of Commons. Part of the reason I know about this is that I actually portrayed the Prime Minister – in a much more flattering manner than you might imagine – during a reenactment of the vote at the Terry Fox Centre in Ottawa, when I participated in the national youth program Encounters With Canada. (That’s also coming up in a future blog post.)

But I also remember Mulroney as a bizarre combination of self-consciousness and frat-house bravado. Determined to escape Trudeau’s shadow while simultaneously attempting to fill political IOUs for everybody from disillusioned Quebec nationalists to Alberta oilmen enraged by the Grits’ ill-conceived National Energy Policy, he seemed desperate for voter validation but also perfectly comfortable in a limo-driven, pin-striped, Gucci-shoe-laden world that only a small percentage of Canadian voters in the ’80s and early ’90s could ever imagine.

It would have been perfect for a nighttime soap opera. Or a Greek tragedy. Or several years’ worth of sketches for The Royal Canadian Air Farce and Double Exposure.

Or, in my case, for a high school student from rural Cape Breton trying to launch a career as a political cartoonist with some crude caricatures for a local weekly newspaper.

This is my first-ever published political cartoon, a bit of self-deprecating frivolity that gave readers of The Port Hawkesbury Reporter two immediate messages when it appeared in the fall of 1988: (1) “Hey, I can’t draw very well but I hope you at least like the punchlines”; and (2) “Boy, our Prime Minister’s got a big chin, eh?” (Five years earlier, in the run-up to his PC leadership victory, reporters asked Mulroney what they thought of his first few appearances in editorial cartoons. He reportedly said, “I love it; I just love what those guys do to my chin,” prompting The Montreal Gazette legend Terry Mosher aka. Aislin to draw a bra cradling the sizeable jaw of a basketball-dribbling Mulroney.)

(Above: Published in November 1989, one year after Mulroney’s second consecutive majority government victory. The bloom was already off the rose by this point; the Tories would plunge to 12 per cent in public opinion polls only a few months later.)

Several Mulroney loyalists came from Atlantic Canada, including the likes of John Crosbie, Bernard Valcourt, and Elmer (“Peter’s Dad”) MacKay, who had stepped aside to allow Mulroney to run in Central Nova and then represented the seat for two more terms after the PC leader chose a Quebec riding for his first two full election campaigns.

Given all this, as well as unqualified support for the Free Trade Agreement from the region’s fishing industry in the 1988 campaign, many of us were baffled by Tory policies that seemed design to punish the East Coast. These included the aforementioned VIA Rail cutbacks, closures of military bases such as CFB Summerside in Prince Edward Island, heavy funding reductions to the CBC that forced the national broadcaster to abandon much of its regional broadcasts, and the 1989 revamping of the federal unemployment insurance program that saw Nova Scotia alone lose $40 million in benefits in a single year. (In the interest of fairness, I should point out that post-Mulroney Prime Ministers such as Jean Chretien and Stephen Harper have also run roughshod over the latter program and, in Chretien’s case, closed more military bases, usually to their own political detriment.)

(Above: Prime Minister Mulroney and Human Resources Minister Barbara MacDougall explain the unemployment-insurance conundrum to confused Nova Scotians. To this day I still can’t believe I was allowed to call our newspaper “The Distorter” instead of its real name, The Reporter. Below: This cartoon was published in December 1990, shortly after another round of CBC budget cuts claimed such Maritime programming as the Sydney-based supper-hour newscast Cape Breton Report.)

Given the current rancour in Canadian political circles over the revised small-business tax structure proposed by the Liberals under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, it’s curious to consider the polarizing effect of another aspect of Mulroney’s legacy, the Goods and Services Tax. Originally proposed as a nine per cent levy and subsequently reduced to seven per cent, the GST launched national outrage that reached a fever pitch when Mulroney stretched Canadian constitutional limits like a worn-out piece of Saran Wrap to ensure the plan cleared the Canadian Senate and became law prior to its January 1, 1991 launch date.

With the Liberals controlling the Upper Chamber – led by a man still deified in certain corners of Cape Breton, former Finance Minister Allan J. MacEachen – Mulroney quickly filled as many Senate vacancies as possible. He sparked a firestorm in Nova Scotia when he named then-Premier John Buchanan, whose government was besieged by RCMP investigations and high-level patronage allegations at the time, as a new Tory Senator. But the howls of protest climaxed when Mulroney used a little-known portion of the Canadian constitution, Section 26 (known colloquially as The Deadlock Clause), to add eight additional Senate seats and subsequently fill them with loyal PC members. On the bright side, the PM made the following cartoon (published in January 1990, one year before the GST’s official launch) somewhat prophetic…

In a bizarre twist, the very liberal tax-and-spend ways of the Mulroney Tories eventually gave way to a Progressive Conservative Party that never met a tax cut or spending reduction it didn’t like. (I lost count of the number of times then-leader Jean Charest and rookie candidate Peter “Son of Elmer” MacKay uttered the words “tax cut” in the 1997 election campaign.)

By that time, mind you, the Liberals under new Prime Minister Jean Chretien were also wearing the GST stain, after backing away from a 1993 election promise to scrap the tax. Instead, the Chretien government convinced the (Liberal) provincial governments of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Newfoundland to accept a blending of federal and provincial levies known as the Harmonized Sales Tax; the idea has since taken hold in other provinces, and today only British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Manitoba administer their own provincial taxes at the retail level. (Quebec oversees the administration of both the GST and its Quebec Sales Tax; Alberta has no provincial sales tax, only the GST – which dropped from seven per cent to five per cent during the decade of power for Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party of Canada.)

I won’t spend too much more time on this topic because, as I’ve already mentioned, Brian Mulroney is going to show up a few more times in this blog. I’ll only make the point that he came into federal politics promising a stronger economy and an end to Canada’s national unity debate, and must have been sorely disappointed when he accomplished neither. (An older, wiser Mulroney recently suggested that he was foolish to make the “jobs, jobs, jobs” pledge that haunted him throughout his days in office.) I’ll also note that his 1984 swings at Liberal patronage under Pierre Trudeau and (briefly) John Turner seem hollow, given the Senate-stacking nonsense described above and a list of plums for loyal Tories that’s far too long for me to even consider documenting here.

However, even in the early ’90s, after years of drawing editorial cartoons at Mulroney’s expense (and enjoying his role in Canada’s political satire), I was struck and even a little dismayed by the disproportionate level of public anger directed towards the man I had known as “Prime Minister” longer than any other. For Christmas 1991, my parents got me a book called Son of a Meech: The Best Brian Mulroney Jokes, as compiled by Yuk Yuks Comedy Club founder Mark Breslin. In his foreword to the book, Breslin noted that Mulroney had emerged as the lightning rod for anything and everything Canadians found annoying or oppressive at that point in our history; high taxes, heavy snow, or the Leafs’ latest losing streak were all “Mulroney’s fault.”

(I only gave the book one read-through, finding myself disappointed by its lack of originality, with Mulroney lazily inserted into decades-old jokes previously designed to smear ethnic groups. In a few rather appalling cases, he was also the punchline to graphic sexual pieces that, even on my angriest teenage days, I wouldn’t have felt comfortable ascribing to a man that I always considered to be a loyal husband, good father of three, and these days, a loving grandfather.)

Today, there are still aspects of Mulroney’s conduct that make me wince a little bit – for example, singing at a Florida reception for newly-elected U.S. President Donald Trump earlier this year, in the midst of a splash of media suggesting he was advising Justin Trudeau on how to deal with The Angry Orange. But in the few other public appearances I’ve seen him make over the past two decades, he’s shown remarkable self-deprecation and a great sense of humour, most notably during his appearances on CBC’s flagship satire series This Hour Has 22 Minutes.

Now, this is not to say that 22 Minutes was kind to Mulroney; I vividly remember a sarcastic fake apology that ran on the series (insisting that “Brian Mulroney is not a ‘sooky baby'”) following the ex-PM’s lawsuit against the Canadian government regarding an RCMP investigation into the purchase of Airbus jets by Air Canada (then a Crown corporation) during his time in office. But during an hour-long 22 Minutes special that ran on New Year’s Eve 1998, Mulroney played a psychiatrist counselling Rick Mercer on guilt feelings resulting from his on-air swipes at the Tories (especially since the Chretien Liberals had proven to be as adept at breaking promises and bungling policy directives as their predecessors). Roughly a decade later, 22 Minutes cast member Gavin Crawford, in character as the show’s geeky teenage correspondent Mark Jackson, breathlessly announced that he was doing an interview “with Ben Mulroney’s dad”; I swear I could almost see the elder Mulroney giggling in response to Crawford’s question about what exactly he’s done with his own life, replying: “Well, you know, I dabbled in politics for a little while.”

And there are still people who admire the way Mulroney “dabbled in politics.” I live a 40-minute drive away from Antigonish, Nova Scotia, the home of St. Francis Xavier University, one of Mulroney’s alma maters. They’re currently tearing down the residence building known as Nicholson Hall and preparing to replace it with Mulroney Hall, which will house a new generation of Canadian leaders to be trained at – I’m not making this up – the Brian Mulroney Institute of Government.

Now, to Mulroney’s credit, the former PM is putting $1 million of his own money into the venture and played a key role in raising an additional $55 million in private donations. The Nova Scotia government is kicking in another $5 million, and StFX president Kent MacDonald told a launch event held nearly a year ago that the university expects to have a combined $75 million raised for the new programs and facilities by the time the doors open in 2020. MacDonald also suggested that “perhaps if Canada is so fortunate,” StFX’s new Institute of Government could dig up “the next Brian Mulroney.”

And so help me, despite everything I’ve described in this blog post (and will also describe in a few future blog posts), I might just show up for the opening day of the Brian Mulroney Institute of Government. I’ll actually leave the old grudges behind; I won’t even bring the darts that I used in the photo that closes out this blog (taken at the home of my university pal Giuliano Valentino three months before Mulroney announced his decision to leave politics).

But, just for old time’s sake, I might bring my sketchbook.

One thought on “Canada 1984: Brian Mulroney – It’s All There, In Black And White”